The processes underlying policymaking can be structured in three main phases: Understanding the challenge that impacts the public (agenda setting), developing policy options (policy formulation and decision making), and reflecting the sentiments and values of the affected parties (policy implementation and evaluation). Scholars have also underscored that policymaking involves policymakers incorporating their own values and beliefs driven by their internalized and externalized perspectives such as their interests (how they think the world should work), ideology (how they would like the world to work) and beliefs (based on their knowledge, how the world actually works). Policymakers involved in formulating health-related policies often encounter public and institutional pressures (including, but not limited to, perceived urgency of the issue). This dearth of evidence is particularly prominent in the context of vaccine scares. While such literature highlights how policymakers perceive challenges and facilitators amid an overarching policymaking process, information that highlights lived experiences amid a broader health-related scare, its fallout, and recuperation is lacking. Similarly, a study among Filipino policymakers on the topic of national-level governance found that several factors inhibited policy development including fragmented leadership and limited multi-sectoral collaboration, which slowed the implementation of a reproductive health law. In a qualitative study in Kenya, researchers underscored the challenges in policy development and implementation in general, particularly in the formulation of tobacco control policies. Literature on policymakers’ perspectives amid other acute, health-related scares (beyond vaccination) has highlighted that resulting policies are not only informed by scientific evidence but also influenced by sociocultural dynamics and community norms. However, there is limited research examining how policymakers perceive, react and – in the longer term – respond to fallout-associated challenges.

Several studies have outlined experiences of frontline medical personnel, such as doctors and community health workers, who encounter this fallout in their daily encounters with clients.

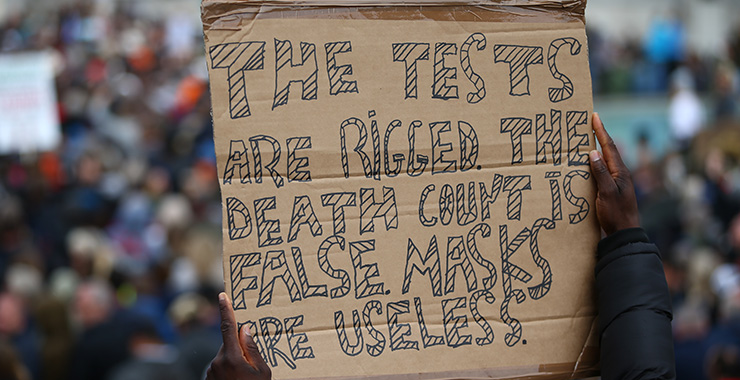

įollowing vaccine scares, personnel engaged in vaccine promotion often find themselves in the challenging position of having to negotiate the scare’s fallout – including a proliferation of misinformation – while continuing to address pre-existing, broader challenges in vaccination rollout. Studies in China and Australia have similarly highlighted how news of a sudden vaccine recall can foster vaccine hesitancy (VH defined as the delay or refusal despite their availability) in the general public. Examples of recent vaccine scares and their fallout include declines in measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine uptake among children in the UK following a retracted article about the risk of autism after vaccination, and drops in general public confidence on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine following reports of serious adverse effects in Japan and Denmark. Current literature highlights that public exposure to vaccine scares can affect public opinion not only regarding the specific vaccine in question, but also regarding vaccination in general, resulting in long-term public health consequences. Vaccine scares, defined as highly publicized discourses on vaccination safety and efficacy, have eroded trust in vaccines in several countries.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)